Beyond the documentary

Understand the Issues

The Bronzeville Neighborhood in Chicago

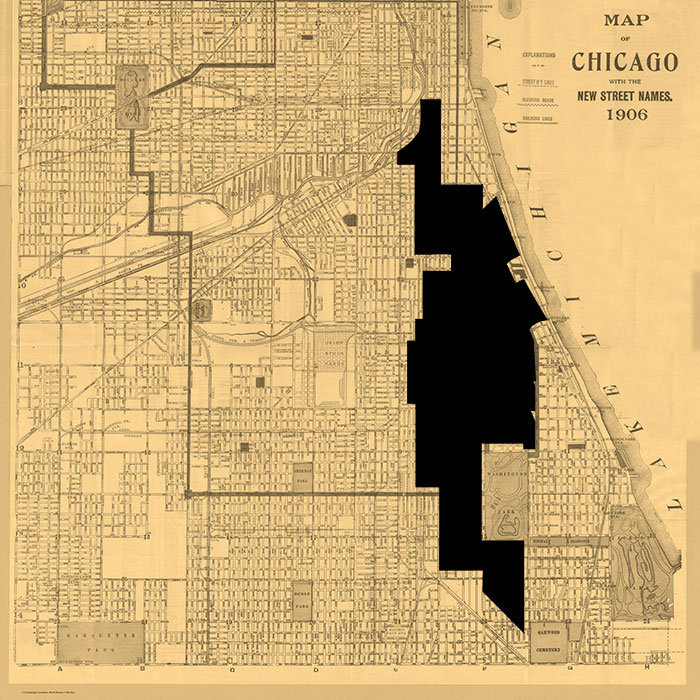

Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood is located on the South Side of the city, in an area historically known as the Black Belt.

Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood is located on the South Side of the city, in an area historically known as the Black Belt.

At the start of the 20th Century harsh discriminatory Jim Crow laws were taking shape in many southern states. As a result, millions of African Americans living in places like Tennessee and Alabama decided to bring their families north in search of a better life. Chicago was a popular northern destination for these families that packed up their belongings to participate in what became known as the Great Migration.

Bronzeville soon became a vibrant African American community with a plethora of black-run shops, businesses, hospitals and schools. It also developed a reputation as a “music mecca” as jazz and blues became extremely popular among both whites and blacks. Bronzeville was home to the one of the most important historic African American owned newspapers, the Chicago Defender, which still publishes today.

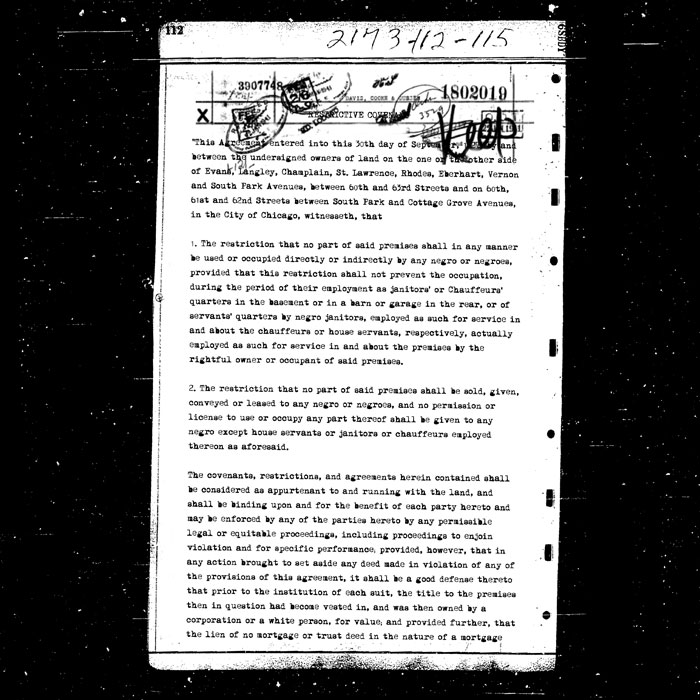

Restrictive Covenants

Although Bronzeville was in many ways a cultural landmark for African Americans all over the United States, it was also became overcrowded, due to racial discrimination. When African Americans arrived in Chicago from the south, they soon realized that they were not welcome in most of the city’s neighborhoods.

Although Bronzeville was in many ways a cultural landmark for African Americans all over the United States, it was also became overcrowded, due to racial discrimination. When African Americans arrived in Chicago from the south, they soon realized that they were not welcome in most of the city’s neighborhoods.

Thanks to restrictive covenants, a set of housing contracts that forbade African Americans from owning or renting property outside of a few select neighborhoods, black Chicagoans were largely boxed in. These restrictive covenants became more and more popular throughout the 1920s after a series of race riots occurred.

By the time restrictive covenants were finally declared unconstitntutiolal by the Supreme Court in 1948, Bronzeville was bursting at the seams with a substantially higher population density than the rest of the city. “Blacks were told, this is where you have to live” resident Valencia Hardy recalls in our documentary.

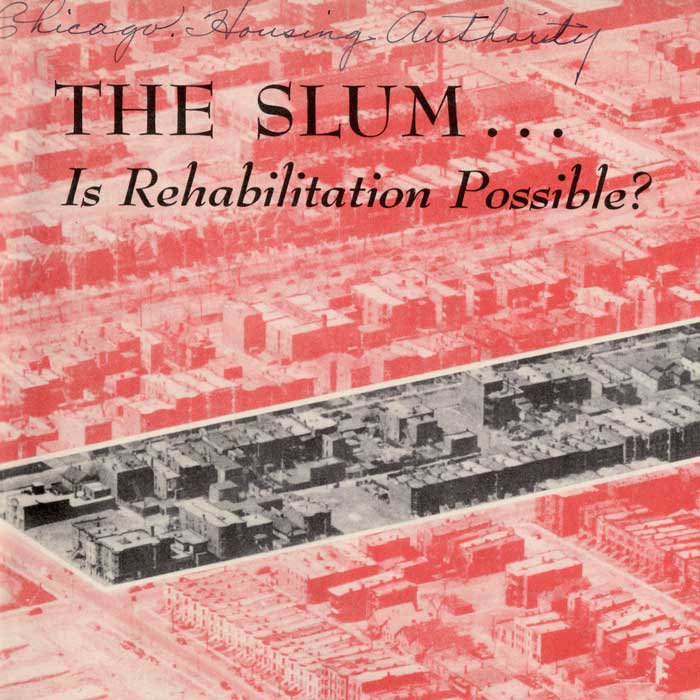

Urban Renewal

With strict restrictive covenants enforcing the boundaries of Bronzeville and its population soaring, disease, crime and poor living conditions began to take hold. Bronzeville’s reputation, once known for its cultural contributions, began to be known for being a “slum.” With an abundance of substandard housing, Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood began to attract the attention of lawmakers.

With strict restrictive covenants enforcing the boundaries of Bronzeville and its population soaring, disease, crime and poor living conditions began to take hold. Bronzeville’s reputation, once known for its cultural contributions, began to be known for being a “slum.” With an abundance of substandard housing, Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood began to attract the attention of lawmakers.

After World War II policy makers began a series of efforts aimed at what they called “urban renewal.” In practice, this meant modernizing dilapidated neighborhoods and often tearing down single family houses and apartment buildings to replace them with ever-larger public housing complexes.

As a result of increased focus on urban renwal, Bronzeville ultimately became home to the largest public housing in the world.

Public Housing’s Rise & Fall

Many of Chicago’s public housing facilities were placed in Bronzeville, owing to its high population of residents under the poverty line. “The projects were good in the beginning,” Bronzeville resident Valencia Hardy says in our documentary film about gentrification in Chicago. With strict standards about who was allowed to rent (no criminal records), and good upkeep, the new buildings were seen by many as a vast improvement over the “slum” housing that predated it.

Many of Chicago’s public housing facilities were placed in Bronzeville, owing to its high population of residents under the poverty line. “The projects were good in the beginning,” Bronzeville resident Valencia Hardy says in our documentary film about gentrification in Chicago. With strict standards about who was allowed to rent (no criminal records), and good upkeep, the new buildings were seen by many as a vast improvement over the “slum” housing that predated it.

However, as time went on many public housing complexes in Chicago became neglected. With a lack of resources facilities like Bronzeville’s Ida B. Wells Homes, Stateway Gardens and Robert Taylor Homes were dilapidated by the 1980s. “I was a property manager in Ida B Wells and man I saw a lot of things…” says Ken Williams, a Bronzeville resident in our documentary. With crime and drugs an evident problem, Chicago’s city government struggled with what to do about the increasingly urgent problem of poor quality public housing in Bronzeville and elsewhere in the city.

The Plan for Transformation

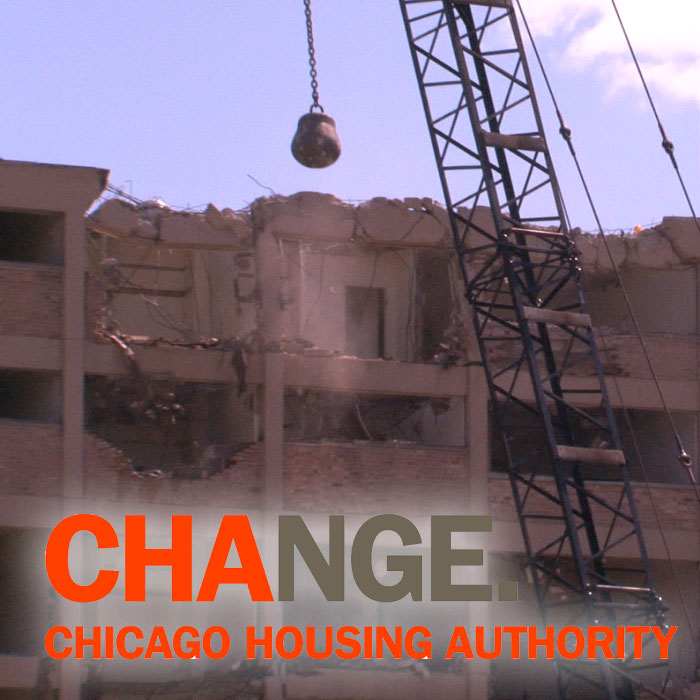

With federal funding and support from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Chicago Housing Authority formed and began its Plan for Transformation in 2000. The Plan called for 25,000 units of public housing to be either replaced or renovated and many of these units were in Bronzeville.

With federal funding and support from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Chicago Housing Authority formed and began its Plan for Transformation in 2000. The Plan called for 25,000 units of public housing to be either replaced or renovated and many of these units were in Bronzeville.

As public housing project after public housing project was torn down, residents were given Section 8 vouchers which enabled them to use housing credits to help pay for private apartments. Meanwhile, demolition on the largest public housing buildings in the country began.

The Plan for Transformation has in many ways been successful, but remains controversial. As Ken Williams explains in our documentary, many of the old problems remain, and some Bronzeville residents find themselves concerned about displacement from their historic neighborhood.

Empty Lots in Bronzeville

With several large public housing facilities torn down, as well as empty lots leftover from dilapidated housing demolitions, Bronzeville found itself with over 2,000 city owned vacant lots by the early 2000s.

With several large public housing facilities torn down, as well as empty lots leftover from dilapidated housing demolitions, Bronzeville found itself with over 2,000 city owned vacant lots by the early 2000s.

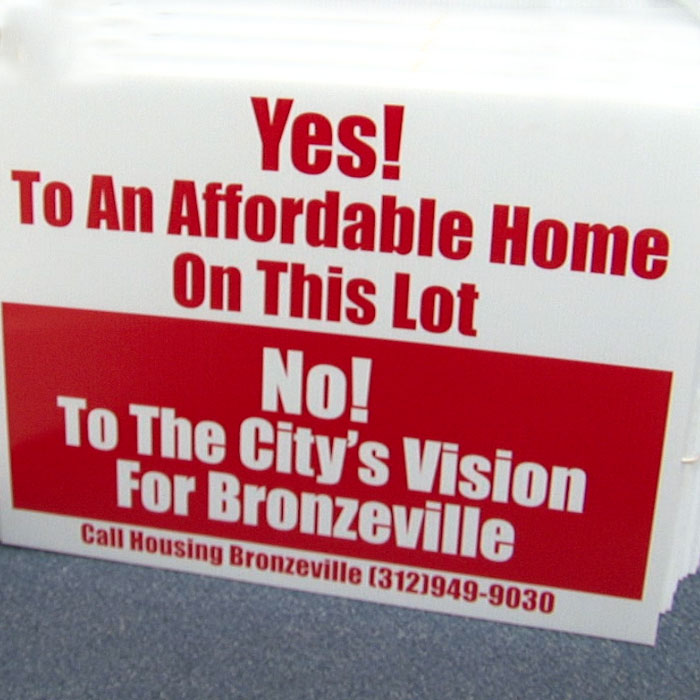

To many Bronzeville residents, these lots represent not just a troubled past but also signs that their neighborhood is being ignored by the city. In several other Chicago neighborhoods the city has sold empty lots to residents for as little as $1, provided the residents took care of them and planned to build upon them. In Bronzeville however, the city initially resisted rolling out that program, with the lots being put “on hold” until further notice.

Housing Bronzeville, a community group project of the Lugenia Burns Hope Center featured in our documentary, seized upon the issue of empty lots as a way to try and get the city to help promote affordable homeownership in their neighborhood. Housing Bronzeville argues that new homes for moderate income families would help create a feeling of investment in their community that would result in lower crime and increased community self-worth. Our documentary chronicles their struggle to get the city to commit to providing empty lots for moderately priced homes to be built upon them in Bronzeville.

In 2018, Chicago announced a program subsidizing new affordable homes on city-owned vacant lots. The Bronzeville neighborhood was not included. Read more about this pilot program.

Gentrification in Bronzeville

As Bronzeville’s public housing projects were torn down and residents scattered to other neighborhoods throughout the city and the suburbs, some private developers have built new single and multi-family housing dwellings in the South Loop and Bronzeville. With this increase in market-rate (non publicly subsidized) housing, there has been an influx of higher income residents in Bronzeville.

As Bronzeville’s public housing projects were torn down and residents scattered to other neighborhoods throughout the city and the suburbs, some private developers have built new single and multi-family housing dwellings in the South Loop and Bronzeville. With this increase in market-rate (non publicly subsidized) housing, there has been an influx of higher income residents in Bronzeville.

Unlike gentrification in many other Chicago neighborhoods, many of the wealthier Bronzeville residents are African American, instead of white. Some wish to return to a historic black neighborhood and others see the redevelopment of Bronzeville as an exciting economic opportunity.

In 1990 the median annual income on the near Southside of Chicago was just $6,804. But by 2000 income had risen to $34,329. New residential developments in Bronzeville sprung up with names like “Bronzeville Pointe” and “Bronzeville Lofts.” Longtime residents like those featured in our documentary began to develop concerns about displacement and gentrification in their storied neighborhood.

The Chicago 2016 Olympics Bid

In the midst of the international housing crash in 2009, the city of Chicago made a bid to host the 2016 Summer Olympic Games.

In the midst of the international housing crash in 2009, the city of Chicago made a bid to host the 2016 Summer Olympic Games.

Chicago’s 2016 Olympic Committee, a private entity separate from City Hall but staffed by many of longtime Mayor Richard M. Daley’s associates, developed elaborate plans to bring the Olympics to town. As part of their bid book to the International Olympic Committee, Chicago 2016 submitted proposals to build new sports venues and redevelop several neighborhoods. Included among them was Bronzeville, which would have been used to both house Olympic athletes and also several sporting events including the construction of a new stadium in Bronzeville’s beloved Washington Park, the largest open land mass on the South Side of the city.

While many Bronzeville residents were excited about the chance to improve their neighborhood, they were also skeptical about promises to prevent displacement of low income inhabitants, and questioned the long term utility of a massive new stadium on the South Side. The community group Housing Bronzeville used the issue of the Olympics as a way to get attention for their affordable homeownership plans from City Hall, as shown in our documentary Blueprint for Bronzeville.

Owning a Home vs Renting

Members of the community group Housing Bronzeville feel that encouraging home ownership for moderate income families would help promote the long term stability and economic fortunes of the Bronzeville neighborhood. They argue that when a resident owns their own home instead of merely renting it, they feel more invested in their community, and more likely to take positive actions to improve it and care for it when their own property values are at stake.

Members of the community group Housing Bronzeville feel that encouraging home ownership for moderate income families would help promote the long term stability and economic fortunes of the Bronzeville neighborhood. They argue that when a resident owns their own home instead of merely renting it, they feel more invested in their community, and more likely to take positive actions to improve it and care for it when their own property values are at stake.

There is some data to support this conclusion: studies find that homeowners are more likely to vote in local elections than renters for instance. Homeowners may also be more involved in neighborhood charitable activity and other things.

Housing Bronzeville states that their goal is returning Bronzeville to a mixed income community as it was during its heyday of the early 20th Century (when it was mixed income because even wealthy African Americans were not allowed to live elsewhere due to restrictive covenants and segregation).